Your cart is currently empty!

A look at Tallahassee’s first Black landowners after the Civil War

Before there was Whole Foods and Lululemon, and even before that, when there was a Miracle 5 movie theater and a Tomato Land produce stand, the land was owned by Henry Watson.

He’s now buried in a small cemetery off of Betton Road called The Plantation Cemetery of Betton Hill. In the back, behind several unmarked graves of enslaved people, lies Watson

Who was he?

Watson was one of the first Black landowners in Tallahassee after the Civil War.

According to the historical marker at the cemetery, Watson was once enslaved by the Winthrop family. In 1860, 75% of the total population in Leon County were enslaved.

The tombstone in the Betton Hills cemetery shows his year of death as 1904. From there, looking at public records, we can infer that he was born in Alabama in the 1840s, but his wife, who was over 20 years younger than him, and his children were all born in Florida.

“Black property owning was diversified across the county in small pockets, more small pockets than you think,” said Jennifer Koslow, a professor of American history at Florida State University.

This includes the land around Lake Hall off of Thomasville Road and where Cascades Park is now, which was once called Smokey Hollow.

The land Watson purchased was also called The Bottom, aptly named because it was at the bottom of the hill. The area wasn’t desirable at the time – the higher the land, the more valuable. Many of the African American landowners bought property in these low-lying areas because these were the places that they could afford and were available to them.

Today, residents of the neighborhood behind Whole Foods remember there used to be a small pond and say every time there’s a heavy rain, the streets are prone to flood.

It wasn’t the norm for freedpeople to be landowners, but Black land ownership does increase in the years after the Civil War, as formerly enslaved people owned nothing before it. Most Black farmers were tenant farmers or share croppers and rented the land they farmed. For some, they ended up paying rent to the same landowners who enslaved them before emancipation.

For share croppers especially, the cycle of debt made it extremely difficult to accumulate money or property.

So it’s notable that Watson, a farmer, owned his own property. His neighbors in the same precinct, precinct 7, also owned land, according to the 1900 Census.

He also wasn’t the only Black property owner in the neighborhood either. His neighbors were farmers, farm laborers and day laborers, according to the census.

Both he and his wife could not read or write, and they had five children: Ben, John, David, Emma and Caroline.

Only the two oldest, Ben, 10, and John, 9, went to school and could not read or write.

Generations of community

On the north side of town, the Maclay House, much of the gardens and all of the land surrounding Lake Overstreet and the northern half of Lake Hall were once owned by African Americans, according to historical research by an FSU graduate student.

“These African-American tenant farmers, plantation employees, and landowners had a historical trajectory that connects them to both antebellum enslavement and contemporary communities. Their history spans the property’s historical period, while the Maclays just forty years in the 20th century,” wrote Triel Ellen Lindstrom in 2008.

While the Maclay family bought his property in 1923, Black Tallahassee residents had been living on that land for generations.

“These hills, these lakes, regardless of who held title, had been the home place of African-American communities connected through marriage, labor and worship since before the Civil War,” Lindstrom wrote.

After the war, by 1868, almost 3,000 Black people owned land in Florida. But most of that land was swampy, low-lying and unfarmable, Lindstrom wrote.

In the decade following the war, Florida was a destination for migrating freed people moving from more developed and older plantation regions of the South, as the land was cheaper than elsewhere.

In Tallahassee, toward the end of the 19th century, many of the white landowners were broke due to emancipation, the boll weevil and declines in the price of cotton.

They sold their property, and the cotton plantations were turned into the vacation homes of wealthy northerners who came down south for quail hunting.

One landowner, however, sold some of his property to six Black families before all this during Reconstruction. Where neighborhoods like Highgrove and Foxcroft sit now used to be a Black community with farm stands, churches and a school.

“It is remarkable that these land purchases were made by people with no monetary assets, and who been enslaved only a couple years before,” wrote a representative from the National Park Service in 2002.

The Edwards, Robinson, Payne, Nelson and Daniels families each paid $500 cash to Mariano Papy, a former state attorney general, for their parcels of land, and later, the Halls paid three installments of $400.

Tobias Payne, who bought land from Papy in 1871, later moved into town.

Today, there is a Payne Street located in Carroll’s Quarters, the neighborhood behind Whole Foods, in the area once owned by Henry Watson.

A priceless purchase

Watson began his land-owning legacy with $100 and a 4-acre purchase from John P. Apthorp in 1883, according to John G. Riley House archives.

In 1897, he bought 1.6 acres from John S. Winthrop for $25, and in 1898, he bought another 3 acres from Apthorp for $75.

The land was all located in section 30 of the county grid, the low-lying area where Miracle Plaza is today.

Finding definitive information on Watson is difficult. There appear to be several Henry Watsons in Tallahassee at the time, and a record of what the Black community was doing, even land purchases, is scarce.

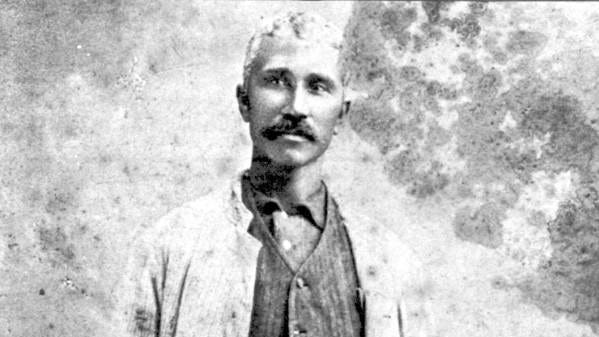

![The accompanying notes with this photo, taken in 1957, state: "Only the bodies of servants of the Winthrop family remain in [this] plot in Betton Hills, which was originally put aside as a burial place for members of the Winthrop family, who came here from North Carolina. The bodies of the Winthrops were moved to the old City Cemetery many years ago."](https://i0.wp.com/www.tallahassee.com/gcdn/authoring/authoring-images/2024/12/27/PTAL/77263579007-td-00377-b.jpg?ssl=1)

“Some communities, people started developing. It had no name, no documentation. Sometimes it was several houses on one parcel of land, and so it wasn’t something that was just documented at that time period,” said Marcus Curtis, a GIS specialist with Leon County.

He and his coworkers have slogged through records and data to plot where Tallahassee’s plantations, oldest cemeteries and neighborhoods once existed.

He said over the last couple of decades, his office has been approached by many families searching for answers about their history, where they come from and where their ancestors may lie.

“Me, personally, I’ve been in these communities. I met these families. I assisted them with a variety of things. These families are in need of service. I’m sympathetic to the situation,” he said.

As for Henry Watson, there’s still a lot we don’t know about him.

There are incomplete archival records. There’s no newspaper record of the year he died, 1904, so there’s no obituary.

The information that could be obtained from the 1890 census doesn’t exist because it was burned up in a fire in Washington D.C., “so we can’t find it that way,” Koslow said.

And state census information isn’t detailed, it’s just numbers.

He also died without a will.

But what we do know is that this land today is considered some of the most valuable property in Tallahassee today, even though once it was called “The Bottom.”

“It was worth something to them even though the land would have been difficult to cultivate. The monetary value would not have been that rich, but the ability to create their own independent life, that doesn’t have a price tag,” Koslow said.

This story is part of TLH 200: the Gerald Ensley Bicentennial Memorial Project. Throughout our city’s 200th birthday, we’ll be drawing on the Tallahassee Democrat columnist and historian’s research as we re-examine Tallahassee history. Read more at tallahassee.com/tlh200. Ana Goñi-Lessan can be reached at agonilessan@gannett.com.

After the Civil War, Tallahassee saw a significant shift in its demographics as newly freed African Americans began to acquire land and establish themselves as property owners. This marked a crucial moment in the city’s history, as it represented a step towards economic independence and self-sufficiency for the Black community.

One such prominent figure was George Proctor, who became one of Tallahassee’s first Black landowners after the Civil War. Proctor, a former slave, worked tirelessly to purchase land and build a successful farm in the area. His story is a testament to the resilience and determination of African Americans in the face of adversity.

Another notable figure was Mary Jane Allen, who also acquired land in Tallahassee after the Civil War. Allen, a widow and former slave, managed to purchase a plot of land and establish a successful farm, providing for herself and her family. Her success served as an inspiration to other African Americans in the community.

The stories of George Proctor and Mary Jane Allen are just a few examples of the many Black landowners who emerged in Tallahassee after the Civil War. Their accomplishments not only helped to shape the landscape of the city but also paved the way for future generations of African American property owners.

As we reflect on Tallahassee’s history, it is important to acknowledge the contributions of these pioneering individuals and the impact they had on the community. Their stories serve as a reminder of the resilience and determination of the Black community in the face of adversity.

Tags:

- Tallahassee Black landowners

- Civil War Black landowners

- Tallahassee history

- African American history

- Reconstruction era

- Black land ownership

- Tallahassee heritage

- Tallahassee historical figures

- African American pioneers

- Tallahassee post-Civil War

#Tallahassees #Black #landowners #Civil #War

Leave a Reply